In a world where connectivity is the universal aspiration, our health information is largely still caught up in silos and, in the main, is not accessible to those who need it – patients, clinicians, researchers, epidemiologists and planners. Shared electronic health records (EHRs) are increasingly needed to support the improvement of health outcomes by providing a timely, comprehensive and coordinated foundation for provision of healthcare. For decades people have been attempting to share health information, but the incremental approach has not been wholly successful – progress has been made, but despite enormous investment and resources, the solution has been found to be more difficult than most anticipated; many well-funded attempts have been stunningly unsuccessful. Healthcare provision appears not to fit the model that has been so successful in other domains such as banking or financial services. Why has sharing health information been so difficult? After all, on the surface, data are, simply, data.

In a world where connectivity is the universal aspiration, our health information is largely still caught up in silos and, in the main, is not accessible to those who need it – patients, clinicians, researchers, epidemiologists and planners. Shared electronic health records (EHRs) are increasingly needed to support the improvement of health outcomes by providing a timely, comprehensive and coordinated foundation for provision of healthcare. For decades people have been attempting to share health information, but the incremental approach has not been wholly successful – progress has been made, but despite enormous investment and resources, the solution has been found to be more difficult than most anticipated; many well-funded attempts have been stunningly unsuccessful. Healthcare provision appears not to fit the model that has been so successful in other domains such as banking or financial services. Why has sharing health information been so difficult? After all, on the surface, data are, simply, data.

Why is the health information domain different?

Health information is the most multifaceted and largest knowledge domains to try to represent in a computer. The SNOMED CT terminology alone has over 450,000 terms expressing health-related concepts, and our collective knowledge about health is far broader, deeper and richer than that required to represent financial systems. The added bonus in health is that our information domain is dynamic - growing and changing as our understanding increases.

Recording, communicating and making sense of health information is something that clinicians do remarkably well in a localised, non-digital world. However the human cognitive processes and assumptions that underpin the traditional health records do not easily translate into the computerised environment. Consider the need for narrative versus structured data; the complexity of clinical statements; use of the same data in a variety of clinical contexts; the need for clinicians to make ‘normal’ or ‘nil significant’ statements, and also the oft underrated positive statements of absence; and the need for graphs, images or multimedia in a good health record. Grassroots clinicians have different personal preferences for creating their clinical records and to support their requirements for direct provision of clinical care and communication to colleagues. In parallel, jurisdictions have different expectations of the grassroots clinical data collection that will support reporting, data aggregation and secondary use of data.

Throw into this mix the complex and convoluted processes required to support healthcare provision; mobile patient populations; and the need for lifelong health records, and it starts to become easier to understand why eHealth has been more of a challenge that many first thought.

Information-driven EHRs

Traditional approaches to the development of EHRs have been software application-driven, hard-coding clinical knowledge into the proprietary data model for each software system and resulting in silos of health information locked away in proprietary databases. This is valuable data, and even more valuable if we can get access to it, exchange it and utilise it. Key stakeholders – patients, clinicians, researchers, planners and jurisdictions – are currently disempowered and are not easily able influence or express their data requirements. We have mistaken the software application for the electronic health record - a classic example of the ‘tail wagging the dog’.

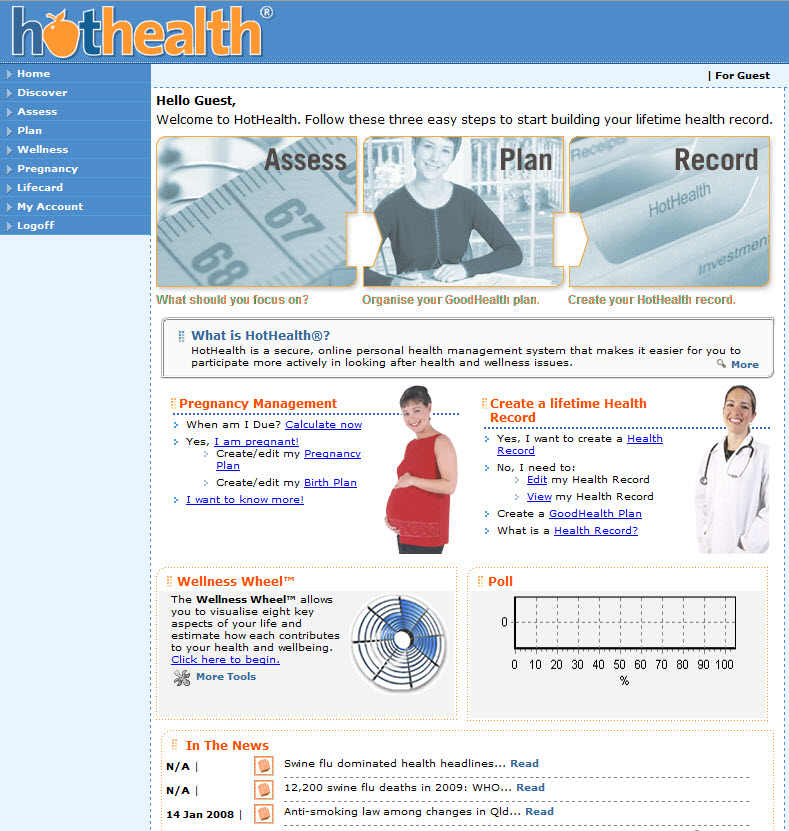

If we focus on the electronic health record being the data, we turn the traditional paradigm upside down. Our EHRs become information-driven by putting the stakeholders at the centre to direct the information content and quality aspects of our EHR systems. It is only then that our systems will be able to reflect the real requirements of stakeholders, ensuring that health information collected data is ‘fit for use’ and will support personal health records, clinician health records and, with appropriate authorisation and permissions, the broadest range of secondary use.

Sharing health information requires common and coherent health information definitions or models – ensuring that health information can be expressed in a way that is meaningful to stakeholders AND that computers can process it. According to Walker et al , Level 4 interoperability, or ‘machine interpretable data’, comprises both structured messages and standardised content/coded data. In practice, it means that data can be transmitted and viewed by clinical systems without need for further interpretation or translation. This semantic, or knowledge-level, interoperability is absolutely required for truly shareable health records, data aggregation, knowledge-based activities such as clinical decision support, and to support comparative analysis of health data. Further, it is only when this health information model is agreed at a local, regional, national or international level, that true semantic interoperability can occur at each of these levels. The broader the level of clinical content model agreement, the broader the potential for semantic health information exchange.

The openEHR paradigm

openEHR is a purpose-built, open source, information-driven electronic health record architecture focused on ensuring that the grassroots health information is recorded clearly, coherently and unambiguously in EHRs, and supporting re-use in other contexts where appropriate. It adopts an orthogonal approach to EHRs - a dual-level modelling methodology with clear separation of the technical from the clinical domains, where software engineers focus on their application development and the clinical domain experts focus on the health information definitions. openEHR focuses on the data - using computable knowledge artefacts known as archetypes and templates to formally express health information.

openEHR archetypes are computable definitions created by the clinical domain experts for each single discrete clinical concept – a maximal (rather than minimum) data-set designed for all use-cases and all stakeholders. For example, one archetype can describe all data, methods and situations required to capture a blood sugar measurement from a glucometer at home, during a clinical consultation, or when having a glucose tolerance test or challenge at the laboratory. Other archetypes enable us to record the details about a diagnosis or to order a medication. Each archetype is built to a ‘design once, re-use over and over again’ principle and, most important, the archetype outputs are structured and fully computable representations of the health information. They can be linked to clinical terminologies such as SNOMED-CT, allowing clinicians to document the health information unambiguously to support direct patient care. The maximal data-set notion underpinning archetypes ensures that data conforming to an archetype can be re-used in all related use-cases – from direct provision of clinical care through to a range of secondary uses.

Templates are used in openEHR to aggregate all the archetypes that are required for a particular clinical scenario – for example a consultation or a report. These can also be shared, preventing more ‘wheel re-invention’. Individual content elements of each maximal archetype can be ‘disabled’ in the template so that the only data elements presented to the clinician are those that conform to national or local requirements and are relevant and appropriate for that use-case scenario. For example, a typical Discharge Summary may commonly comprise 10 common archetypes; templates allow the orthopaedic surgeon to express a slightly different ‘flavour’ of the Discharge Summary based on which elements of each archetype being either active or disabled, compared to that required by a Obstetrician who needs to share information about both mother and newborn. One ‘size’, or document, does not fit all. The archetypes, as building blocks, are the key to semantic interoperability; while templates allow flexible expression of the archetypes to fulfill use-case requirements.

How achievable is this? Only ten archetypes are needed to share core clinical information that could save a life in an emergency or provide the majority of content for a discharge summary or a referral. If each archetype takes an average of six review rounds to reach clinician consensus and each review round is open for 2 weeks, it is possible to obtain consensus within an average of three months per archetype – some complex or abstract ones may be longer; other simpler, more concrete archetypes will be shorter. Many archetypes are already well developed in the international arena and within national programs. As archetype reviews can be run in parallel, a willing community of clinicians could achieve consensus for core clinical EHR content within three to six months.

It is estimated that as few as fifty archetypes will comprise the core clinical content for a primary care EHR, and maybe only up to two thousand archetypes for a hospital EHR system including many clinical specialties. The initial core clinical content will be common to all clinical disciplines and can be re-used by other specialist colleges and interested groups. More specialised archetypes will gradually and progressively be added to enhance the core archetype pool over time.

The openEHR Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM) is an online clinical knowledge management tool – www.openEHR.org/knowledge - which provides a repository for archetypes and other clinical knowledge artefacts, such as terminology subsets and document templates. Based on a data asset management platform it provides a clinical knowledge ecosystem supporting the publication lifecycle and governance of the archetypes. Within CKM, a community of grassroots clinicians and health informaticians collaborate in online reviews of each archetype until consensus is reached and the agreed archetype content is published. Clinicians and other domain experts need no technical knowledge to engage with archetypes - the technical aspects of archetypes are kept hidden ‘under the bonnet’ – but they use their expertise to ensure that the content definitions within each archetype is correct and appropriate. Each content review is conducted online at a time of convenience to the clinician and usually only takes five to ten minutes for each participant. Thus the clinical domain experts themselves drive the archetype content definitions, and CKM has become a peer-reviewed knowledge resource for all parties seeking shared, standardised and computable health information models.

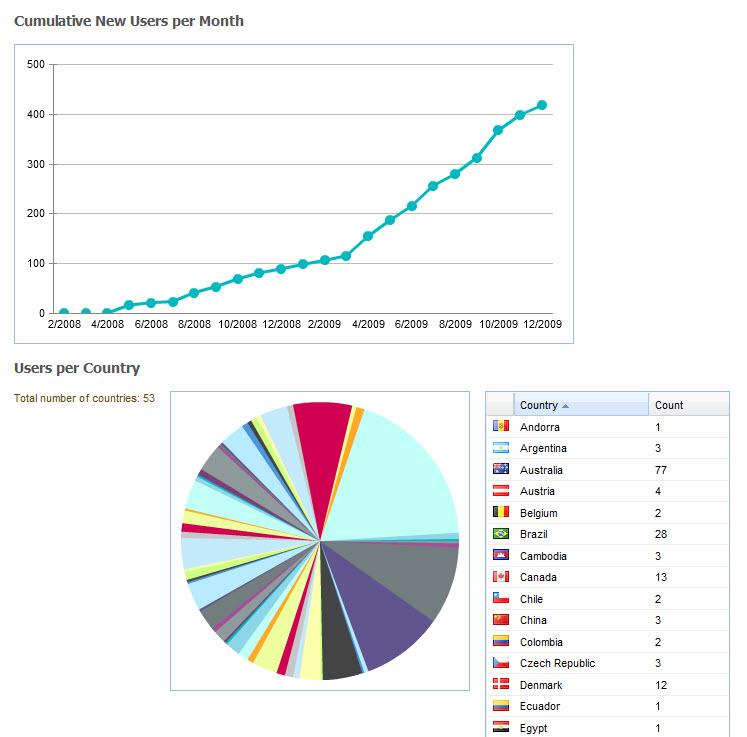

At the time of writing CKM has acquired, largely by word of mouth, 565 registered users from 62 countries, including 181 people who have volunteered to review archetypes, and 73 who have volunteered to translate archetypes. The repository contains 273 archetypes, of which 15 have content that are in team review and 9 published. Two example templates have been uploaded, and we await final publication of the openEHR template specification before we expect to see template activity increase. Terminology subset functionality has been added only recently and our first terminology subsets uploaded. So, while CKM is still relatively new, its Web2.0 approach to artifact collaboration and publishing, combined with formal knowledge artifact governance positions CKM as a pioneering ‘one stop shop’ for clinical knowledge resources online.

Current CKM functionality includes:

- Display of artefacts including structured views, technical representations and mind maps to make it easy for clinicians and others to review;

- Uploading of new knowledge artefacts – archetypes, templates and terminology subsets – for review and publication;

- Archetype metadata supporting classification, ontological relationships and repository-wide searches;

- Digital asset management including provenance and artefact audit trail;

- Integration with openEHR tools supporting quality assessment & technical validation checks;

- Review and publication process for clinical content – draft, team review, published and reassess states

- Terminology binding and terminology subset reviews;

- Online archetype translation with review;

- Community engagement via threaded discussions, repository downloads, attached resources, watch lists, email notifications, user dashboards and release sets;,

- Editorial support via To Do lists, user and team administration, review management, artefact modification, classification management, broadcast emails etc;

- Subscriber auto-notification including Twitter and email

- Reports – Archetypes, Templates and Registered users

A governed repository of shared and agreed archetypes will provide a ‘glide path’ towards full semantic interoperability of health information; a clear forward path for standardisation of data definitions. These will bootstrap new application or program development, provide a ‘road map’ to support gradual transition of existing systems to common data representation and provide the means to integrate valuable silos of legacy data.

Benefits of a collaborative, data-driven approach

A collaborative and domain expert-led approach to our health information provides many benefits which include the following.

Benefits for stakeholders

- Active involvement of domain experts to ensure the safety and quality of health information.

- Development of a coherent set of health information definitions:

- Improved data quality – shared core clinical content plus specialised domain-specific content will be agreed and ratified by the domain expert community; health information created will need to conform to the agreed archetype specifications.

- Improved data ‘liquidity’ – specifications to support exchange, flow and re-use of health information - from direct patient care through to secondary use of data. Improved data longevity – shared non-proprietary health information definitions minimise need for data transformations or system migration and the inherent risk of data loss; will support the cumulative, lifelong health records and longitudinal data repositories;

- Improved data availability – easier integration of health information from disparate sources when based on common archetype definitions;

- Re-use, integrate and aggregate data for supporting quality processes such as clinical audit, reporting and research; and

- Break down the existing ‘silos’ of health information based on proprietary and varied definitions.

- Online collaboration maximises the potential for a breadth of grassroots stakeholder engagement in ensuring correctness of the health information definitions.

- Active participation by clinical domain experts to shape and influence their EHRs, ensuring that EHR content is ‘fit for clinical purpose’.

- Online participation in clinical content review will be of short duration and at times of convenience to the clinician, avoiding the significant time and opportunity cost of attendance at face-to-face meetings.

Benefits for patients

- Data created and stored in a shared, standardised and non-proprietary representation supports the potential for application-independent data records that can persist for the life of the patient.

- Improved data ‘liquidity’ – so that data can flow between healthcare providers and systems to where the patient needs it.

Benefits for national programs and other jurisdictions

- Development of a coherent national set of clinical content specifications to support the shared EHR programs, health information exchange and secondary use.

- Enables national governance of foundation clinical content while at the same time facilitates flexible expression of local domain requirements

- Efficient use of sparse clinical, informatics and stakeholder resources:

- Design & create an archetype once; re-use many times;

- Leveraging existing clinical specification work done internationally to improve local national pool of archetypes;

- Online collaboration maximise the potential for stakeholder engagement at the same time as minimising the requirement for expensive face-to-face meetings; and

- Review and publication of agreed clinical specification definitions within weeks to months;

- Review and standardisation of clinical documents containing agreed archetypes will be relatively short.

- • Clinical knowledge management ecosystem:

- Single national repository of clinical knowledge artefacts, including archetypes and terminology subsets.

- Focussed and coordinated knowledge management environment where all stakeholders can observe, participate and benefit; the opposite of the current fragmented, isolated and proprietary approach to defining health information content.

- Digital knowledge asset management:

- Manages authoring, reviewing, publication and update lifecycle of all knowledge assets;

- Provenance and asset audit trails;

- Ensures asset compliance to quality criteria;

- Ensures technical validation of assets; and

- Development of coherent release sets for implementers;

- Governance of knowledge assets.

- Distribution of knowledge assets via coherent release sets.

- Removes the need for per message or per document negotiation between application developers, organisations and jurisdictions each time information needs to be integrated or exchanged by use of the standardised content within more generic message wrappers or document structures.

- Transparency of editorial and publishing processes; accountability to the domain expert community itself.

- Precludes the need for ratification of clinical or reporting documents through a traditional standards process when they consist of subsets of the nationally agreed archetypes.

Benefits for application developers

- Download coherent sets of clinical content definitions from a published and agreed national repository – not re-inventing the wheel by defining each piece of health information over and over.

- Software development remains focused within the expert technical domain – user interface; workflow processes; security, data capture, storage, retrieval and querying; etc.

- Removes the need for per message or per document negotiation between vendors, organisations and jurisdictions each time information needs to be integrated or exchanged by use of the standardised content within more generic message wrappers or document structures.

Benefits for secondary users of data

- Existing data can be mapped to archetypes once only, and transformed into a validated and consistent format; new data can be captured and aggregated according to the same national archetype definitions.

- Data stored in a common representation can be more easily aggregated and integrated.

- Access to valuable legacy data that would otherwise be unavailable.

Agreed and shared representations of the health information, embracing existing stakeholder requirements and developed rapidly by an active online community, will kick-start and accelerate many currently fragmented eHealth activities. Sharing archetypes as the definition of our health information will not only provide a common basis for recording and exchanging health information but also simplify data aggregation of data, support knowledge-based activities and comparative data analysis. Perhaps even more compelling, we are making certain that our domain experts warrant that the data within our EHRs, and flowing between stakeholders, is safe and 'fit for purpose'.