Despite some wins, the transition to EHRs has generally been much slower than we anticipated, much harder than we imagined, and it is not hard to argue that interoperability of granular health data remains frustratingly elusive.

"Smart data, smarter healthcare"

Bridging the interop chasms

EHR building blocks

For many years I have borrowed an analogy using Lego building blocks rather than the notion of generic 'shapes' - that if we get the foundation building blocks agreed and fit for use in our EHRs (ie clinical archetypes), then they can be re-used in multiple contexts and combined in any permutation or combination to represent the clinical documentation that we need.

Clinical modelling, openEHR style

The outcome of a program of coordinated clinical content standardisation provides a long term and sustainable national approach to developing, maintaining and governing jurisdictional health data specifications. It can form the backbone for a national health data strategy and is a key way to ensure that clinicians contribute their expertise to jurisdictional eHealth programs.

Preventing health data 'black holes'!

It really is not surprising that scientific data is disappearing all the time. But, oh, think of the value of this data - in terms of cost and knowledge. Irreplaceable. The original article from Smithsonian.com is here: The vast majority of raw data from old scientific studies may now be missing.

Some excerpts:

A new survey of 20-year-old studies shows that poor archives and inaccessible authors make 90 percent of raw data impossible to find.

...

When a group of researchers tried to email the authors of 516 biological studies published between 1991 and 2011 and ask for the raw data, they were dismayed to find that more 90 percent of the oldest data (from papers written more than 20 years ago) were inaccessible. In total, even including papers published as recently as 2011, they were only able to track down the data for 23 percent.

...

"Some of the time, for instance, it was saved on three-and-a-half inch floppy disks, so no one could access it, because they no longer had the proper drives," Vines says. Because the basic idea of keeping data is so that it can be used by others in future research, this sort of obsolescence essentially renders the data useless.

...

And preserving data is so important, it's worth remembering, because it's impossible to predict in which directions research will move in the future.

Seems to me that the openEHR approach to data definitions is an excellent candidate for preventing the health data 'black hole' too!

Non-proprietary, open data specifications are a key component for future-proofing irreplaceable clinical and research data.

Standards Development?

https://twitter.com/psujorge/status/438909282499977216

Technical/Wire...Human/Content

In a comment on one of my most recent posts, Lloyd McKenzie, one of the main authors of the new HL7 FHIR standard made a comment which I think is important in the discourse about whether openEHR archetypes could be utilised within FHIR resources. To ensure it does not remain buried in the rather lengthy comments, I've posted my reply here, with my emphasis added.

Hi Lloyd,This is where we fundamentally differ: You said: "And we don’t care if the data being shared reflects best practice, worst practice or anything in between."

I do. I care a lot.

High quality EHR data content is a key component of interoperability that has NEVER been solved. It is predominantly a human issue, not a technical one - success will only be achieved with heaps of human interaction and collaboration. With the openEHR methodology we are making some inroads into solving it. But even if archetypes are not the final solution, the models that are publicly available are freely available for others to leverage towards 'the ultimate solution'.

Conversely, I don't particularly care what wire format is used to exchange the data. FHIR is the latest of a number of health data exchange mechanisms that have been developed. Hopefully it will be one that is easier to use, more widely implemented and will contribute significantly to improve health data exchange. But ultimately data exchange is a largely technical issue, needs a technical solution and is relatively easy to solve by comparison.

I'm not trying to solve the same problem you are. I have different focus. But I do think that FHIR (and including HL7 more broadly) working together with the openEHR approach to clinical modelling/EHRs could be a pretty powerful combo, if we choose to.

Heather

We need both - quality EHR content AND an excellent technical exchange format. And EHR platforms, CDRs, registries etc. With common clinical archetypes defining the patterns in all of these uses, data can potentially start to flow... and not be blocked and potentially degraded by the current need for transforms, mappings, etc.

The Questionnaire Challenge

How should we model questionnaires in our health data? This is something that @ianmcnicoll and I have grappled with for years. We have reached a conclusion in recent times, and our approach, perhaps rather controversially, is not to model them! Yes, you read me right - as a general principle, don't archetype questionnaires.

Now of course there will be some situations where there are standardised and ubiquitous questionnaires and perhaps it will be reasonable to lock these down as fixed data elements and value sets in an archetype, and maybe even govern them within a CKM environment.

But... Consider the number of questionnaires out 'in the wild' at any point in time. Should each of these be archetyped?

Let's think it through. If there are 5000 questionnaires in the world (and clearly there are way more questionnaires than that out in the health ecosystem) then we would need a corresponding whopping 5000 archetypes. And, as we all know, no two questionnaires will be alike even if they have a common parent document - it is always human nature to 'tweak' each one for local use because 'our situation' is unique. It's just the way it is. The consequences are that any data captured using the myriad of archetypes, even though they may be similar, the data will not be interoperable. We will have a huge number of archetypes with a huge variation in content and intent - not a lot of upside from my point of view.

Another alternative could be to define a generic archetype pattern for a questionnaire, and re-use that. In fact we tried this back in 2007 with our work in the NHS - you can see a reasonable example here. The resulting questionnaire pattern is pretty simple and relies on using the templating layer to document the questions, and either templating or use of a terminology subset to record the answers. The equivalent FHIR resource appears similar in principle and intended use. This kind of pattern provides a common framework for a questionnaire but really doesn't give us a lot more interoperability for questionnaire data - the actual questionnaire content will vary enormously and the results can still be chaotic.

So, still somewhat clunky and awkward - not an elegant solution at all.

Then we got to thinking: Do we always need to actually record the questions and their answers in the EHR? This is a critical question. Sometimes the answer is yes, but most often I think we will find that we don't need to record the actual question and (often) check box response. What we really want to record is the outcome, the real health information meaning.

Think about the practical aspects of this...

Clinicians have a systematic questioning process for history taking - we all have a similar pattern but ask subtly different questions - resulting in zillions of permutations and combinations and levels of granularity. Questions could range from: "Have you had any abdominal symptoms?" to "Have you had any nausea, vomiting, reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation etc" to whatever combination is relevant for a given clinician in a given clinical situation. Many will ask the same kind of question slightly differently. Every resulting questionnaire will be slightly different.

And what do they record? They don't record each question and corresponding Yes/No answers in their paper health records. They record the positive responses or the relevant negatives, and/or maybe a quick note that there were no positive responses to systematic questioning about current symptoms, problems, past history, family history etc.

So we need to ask ourselves: Do we need to record the exact question, the potential alternative answers and the actual answer?

If the answer is yes, then it is a very good reason to lock in the questionnaire in an archetype, or at least a template.

If the answer is no, then what is the best way to record the relevant data - the relevant positives and the relevant negatives. For example, with abdominal pain - record the details about their diarrhoea and colicky pain in the right lower abdomen, PLUS that the patient has NEVER had an Appendicectomy.

So I'm suggesting that we need to record the positive presence of something identified in the questionnaire, for example a symptom, diagnosis or previous procedure, and the positive absence of related things. In this case, record the details about the diarrhoea and abdominal pain as the positive presence of symptoms using the Symptom archetype and positive exclusion of a previous Appendicectomy procedure in the Exclusion of Procedure archetype. We don't need to record the actual question and corresponding Yes/No answer.

So our current approach in Ocean is to use the software UI as the means to display the checklist or questionnaire, but only record in the electronic health record any relevant answers - both the positive presence of symptoms, signs, diagnoses, procedures and tests etc, and also the positive exclusion of any of these things - all using standardised archetypes.

Lets face it, it is not often that we ever go back to look at the raw questionnaire data again. So now we tend not to record the raw data (with some exceptions, where it may be required or useful) but use a transform so that a patient's or clinician's positive tick in a box for 'Past History of Epilepsy?' will be converted into a positive statement of 'Epilepsy' within an EHR, using the Diagnosis archetype. Any additional 'other' free text or 'details' or 'date of diagnosis' from the questionnaire can be captured using other relevant data fields for the Diagnosis archetype. The benefit from this approach is that this data can then be potentially re-used into the future as part of a comprehensive Problem List, not just buried as a ticked check box within a questionnaire from years ago, perhaps never to see the light of day ever again.

Consider the questionnaire as what it really is - just a clinical communication tool, a checklist. It is absolutely not the best means to record, persist and re-use good quality health data. What we really want to record in a consistent way are those critical pieces of health information in a formal archetype so that the data can be utilised for long term health records, decision support, exchange or analysis. Recording the check boxes answers from a questionnaire don't really do that job!

Archetypes in the Real World

I've spent the past week in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Ian McNicoll (@ianmcnicoll) and I were been training clinicians about archetypes and clinical knowledge governance, ready for the launch of their national CKM. A highlight was a side trip to visit the state-of-the-art Paediatric Intensive Care Unit in Ljubljana. The electronic health record has been running there now for two years, with electronic processes gradually taking over. I was escorted by the clinician in charge of the ICU, Professor Kalan. The purpose of the visit – for him to meet someone who facilitated the archetypes used to run his EHR and for me to see our collective international archetype work implemented and used for real clinical purposes, largely under the expert clinical informatics guidance from Ian.

I was thrilled and a little taken aback, all at once. It is one thing to sit in an office researching clinical models and then to remotely collaborate with our international archetype community. But it is another to see real-time data being collected half a world away from home and knowing that we all had a small part in this, especially to support such critical care for a newborn baby. In the photo, above, you might just be able to spot a humidicrib surrounded by all of the equipment.

The majority of these archetypes were built by the international openEHR community for various projects and now utilised under the CC-BY-SA license by the EHR company to develop their clinical system. There are some local archetypes in use as well – added for practical and pragmatic purposes - but these are very much in the minority. These same international archetypes are also being used in the EHR repository in the Northern Territory, Australia, and are underpinning their current work on shared antenatal care and hearing health programs. Soon this work is to be extended for renal failure and heart disease. And across more than 20 sites in Australia we have an infection control system that is using both archetypes and some that have been built specifically to support infection control activities and outbreak management. These shared archetypes are also underpinning work in UK, Brazil, Japan and Sweden.

Next week Ian and I are in Norway to support the Norwegian national archetype effort – training their clinicians and informaticians about archetypes, and especially governance principles at a national level.

There are now 5 CKMs in existence:

- the openEHR international CKM;

- Australia;

- City of Moscow;

- UK clinical community; and the brand new

- Slovenian eHealth program CKM.

The international CKM will continue to gather quality archetypes from all sources and coordinate international review and modelling activities. The intent is for this CKM to be the first port of call for those looking for an archetype.

The national-, organisation- or program-based CKMs will be focussed on supporting local health IT activities and will leverage the international pool of archetypes by a virtual 'read only' reference capability as well as hold specific local archetypes or modifications of the international archetypes that will support local implementation.

Above all the aim is to create high quality, computable, clinical content definitions that have been developed and ratified by the clinicians themselves. In turn this will support collection of good quality data that can be used for a variety of purposes – ranging from the health record itself; through querying and knowledge-based activities such as decision support; aggregation, analysis and research; and secondary use, including population health activities.

I have said it before, but let me say it again…

IT. IS. ALL. ABOUT. THE. DATA.

In the discussions about standards, the standardisation of data is usually missed.

Seeing this little baby in a humidicrib in amongst all of the 'machines that go beep' has invigorated me again.

Let's continue, and even accelerate, our collaboration on the development of archetypes. This will enable us to gather the data we need to provide the kind of healthcare our patients deserve.

Engaging clinicians: building EHR specifications

There is a methodology that is pragmatically evolving from my experience in openEHR clinical modelling work over the past few years. It has developed in a rather ad hoc way, and totally in response to working directly with clinicians. The simplicity and apparent effectiveness – both for me and the clinicians involved - continues to surprise me each time I use it. The clinical content specifications for specialised health records and care plans that we are building are being developed with a sequence of expert input and clinical verification:

- Identifying the clinical requirements and business rules in conjunction with a selected initial domain expert group;

- Broader abstract verification of the notion of ‘maximal data set’ for ‘universal use case’ during formal archetype review cycles;

- Contextual validation during template review by ‘on-the-ground’ clinicians; and finally, although to a lesser degree,

- Validation during mapping and migration of legacy data.

With each project I am refining this process. Starting off a project with face-to-face meetings has been a ‘no brainer’ – after all, it takes a while for everyone to understand the get the idea of what we are doing. However after initial workshops, pretty much everything else can be done via web conference, online collaboration via CKM and email.

I find the initial workshops are usually greatly satisfying. Within hours we can be creating two outputs – a mind map that reflects the clinicians evolving conversation about their requirements and, in parallel, an equally agile template of clinical content specifications that can be verified by the clinicians in real time.

The mind map is displayed on a shared screen or via a data projector and acts as a living document, evolving as we talk through the clinical requirements, and identify the complexities, dependencies and relationships of all the components. The final mind map may be surprisingly different to how it started, and at the end of the conversation, the clinicians can verify that what they’ve said if accurately reflected in the mind map. It is an open source tool, so we can also share this around after the workshop for further comments.

Most recently I have begun building a template on the fly during the workshop, using any existing archetypes that are available, and identifying gaps or the need for new archetypes on the mind map as we go. In this way we are actually building the content specification in front of the clinicians as well. They get an understanding of how the abstract discussion will actually shape the resulting EHR content and they can verify it as we gradually pull it together. The domain experts are immediately equipped to answer the question: “Does this specification match what you have been telling me you do in practice?”

This methodology seems to bring the clinicians along with us on the clinical modelling journey, and most are able to understand at least some of the implications of some of our requirements discussions and, in particular, the ‘shape’ of the data that we can collect. It is a process seems to suit the thinking process of many clinicians and the overwhelmingly consistent feedback from recent workshops is that they have all actually enjoyed the experience and want to know what are the next steps for them to be involved. So that’s certainly a winner.

And the funders/jurisdictions are anecdotally confirming for me that they are finding that this approach is supporting higher quality specifications in a much shorter time frame.

For example, at a project kickoff workshop for a new project recently, in two days we:

- developed a series of mind maps capturing a consensus view of the clinical requirements and business processes;

- identified all the archetypes required for the entire project, including those that existed and were ‘fit for use’, those that needed some extension to meet requirements and new archetypes that needed to be created;

- identified sources of information or mind mapped the requirements for each new archetype identified; and

- built 3 templates comprising all of the existing archetypes available from a number of sources – the NEHTA CKM http://dcm.nehta.org.au/ckm/, the openEHR international CKM http://www.openehr.org/ckm/ and local drafts that I had on my own computer. For a number of the new archetypes we also collectively identified source information that would inform or be the basis for the archetype development.

All of this described above took 8 medical practitioners clinicians away from their everyday practice for only 1-2 days, each according to their availability. Yet it provided the foundation for development of a new clinical application.

Then I go home. Next steps are to refine the mind map, modify/update/specialise any archetypes for which we have identified new requirements and build the new ones. And in parallel start the collaborative process through a CKM project to ensure that existing and modified archetypes are ‘fit for (our project’s) purpose’, and to upload and initiate reviews on the new draft archetypes.

All work to progress these archetypes to maturity (ie aiming for clinical consensus) and then validate the templates as ready for handover to the implementers can be done online, asynchronously and at a time convenient to the clinicians work/life balance!

I live over 2000 kilometres away from these clinicians. Yet the combination of web conference and CKM enables us to operate as an ongoing collaborative team. It seems to be working well at the moment... No doubt I'll continue to learn how to do it better.

"We have the capability!"

We have had the technology for a purpose-built openEHR-compliant 'plug & play' platform for some time; standalone applications have been built, but just recently it appears that the practical reality of an multi-application platform is also about to happen. "We have the technology. We have the capability..." Stay tuned.

...Reminds me of my 1970's hero, Steve Austin, the Six Million Dollar Man. With apologies to Steve:

"We have the technology. We have the capability to make the world's first universal health platform. openEHR will be that platform. Better than ever before. Robust health data...application independent...semantically interoperable!"

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7zNY0I5JNI&w=480&h=360]

Preserving health data integrity

How valuable do we really think health data is? How seriously do we take our responsibility to preserve the integrity of our health data? Probably not nearly as much as we should.

Consider the current situation of most clinicians or organisations when purchasing a clinical EHR system. What do they look for? Many possible answers are obvious, but there is one question that I suspect very few are asking. How many consider what data they will be able to export and convert to another format, preserving the current data integrity, at the end of the typical 5-10 year life span of the application? Am I wrong if I suggest it is not many at all?

Despite all the effort that we clinicians put into entering detailed data to create a quality health record we don't seem to often consider the " What next?" scenario. How much and precisely what data will we be able to safely extract, export, transfer or convert into the next, inevitable, clinical system? Ironically, we are simultaneously well aware that clinical systems have a limited technical life span.

Any and all of the health data in a health record is an incredibly valuable asset to the holder, to the patient (if these are not the same entities) and to those downstream with whom we may share it in the future - in terms of $$ invested; manpower resources used to capture, store, classify, update and maintain it; and not least the future value that comes from appropriate and safe clinical decisions being made upon the integrity of existing EHR data.

Yet we don't seem to consider it much... yet. However, as more clinicians are creating increasing amounts of isolated pockets of health data, we should be thinking about it very hard.

Every time we change systems we put our health data at risk - risk of absolute data loss and risk of possible corruption during the conversion. The integrity of health data cannot be guaranteed each time it is ported into a new system because current methods always require some kind of intervention - mapping, transformations, tweaking, 'cleaning', etc. Small errors can creep in with each data manipulation and which over time, can compromise the safety and value of our health data. On principle we know that the data should not be manipulated, but being limited by our traditional approach to siloed EHR applications, we have previously had little choice.

We need to change our approach and preserve the integrity of our health data at all costs. After all it is the only reason why we record any facts or activity in an electronic health record - so we can use the data for direct patient care; share & exchange the data; aggregate and analyse the data, and use the data as the basis for clinical decision support.

We need to change our approach and preserve the integrity of our health data at all costs. After all it is the only reason why we record any facts or activity in an electronic health record - so we can use the data for direct patient care; share & exchange the data; aggregate and analyse the data, and use the data as the basis for clinical decision support.

We should not be focused on the application alone.

Apps will come and go, but we want our health data to persist - accurate and safe for clinical use - beyond the life span of any one clinical software application.

I've said this before, but it's worth saying many times over:

It's. all. about. the. data.

One of the key benefits of the openEHR paradigm is that the data specifications (the archetypes) are defined independently of any specific clinical system or application; are based on an open EHR architecture specification; and are publicly available in repositories such as the Clinical Knowledge Manager. It means that any data that is captured according to the archetype specification is directly usable by any and all archetype-compliant systems. Plus the data is no longer hard-wired into a proprietary application so that it is orders of magnitude easier to accurately share or transfer health data than it has before.

Clinical system vendors that don't directly embrace the archetype-technology may still 'archetype-aware', and can choose to use the archetype specifications as a means to understand the meaning of existing archetyped data and integrate it appropriately into their systems. Similarly they can map from their non-openEHR systems to the archetype specifications as a standardised method for data export and exchange.

The openEHR paradigm enables potential for archetype-compliant systems to share the same archetyped data repository - along the lines of an Apple platform 'plug & play' approach, with applications being added, removed or updated to suit the needs of the end-users, while the data persists intact. No more data conversions needed.

Adapted from Martin van der Meer, 2009

Now that's good news for our health data.

To HIMSS12... or bust!

This blog, and hopefully some others following, will be about my thinking and considerations as I man an exhibition booth at the huge HIMSS12 conference for the first time next month… Well, we’ve committed. We’re bringing some of the key Ocean offerings all across the ocean to HIMSS12 in Las Vegas next month. If it was just another conference, I wouldn’t be writing about it. But this is a seriously daunting prospect for me. I’ve presented papers, organised workshops, and run conference booths in many places over the years – in Sarajevo, Göteborg, Stockholm, Capetown, Singapore, London, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne – but this is sooooooo different!

The equivalent conference here in Australia would gather 600-800 delegates, maybe 40-50 exhibition booths. Most European conferences seem to be a similar size, admittedly these are probably with a more academic emphasis, rather than such a strong commercial bent, which might explain some of the size difference. By comparison, last year’s HIMSS conference had 31,500 attendees and over 1000 exhibition booths – no incorrect zeros here - just mega huge!

I can’t even begin to imagine how one can accommodate so many people in one location. I have never even visited HIMSS before – we are relying heavily on second hand reports. You may start to understand my ‘deer in headlights’ sensation as we plan our first approach to the US market in this way.

Ocean's profile is much higher elsewhere internationally. Our activity in the London-based openEHR Foundation and our products/consulting skills have a reasonable profile in Australia and throughout much of Europe; and awareness is growing in Brazil as the first major region in South America. In many ways the US is the one of the last places for openEHR to make a significant impression – there are some pockets of understanding, but the limited uptake is clearly an orthogonal approach to the major commercial drivers in the US at present, however we are observing that this is slowly changing... hence our decision to run the gauntlet!

openEHR’s key objective is creation of a shareable, lifelong health record - the concept of an application-independent, multilingual, universal health record. The specification is founded upon the the notion of a health record as a collection of actual health information, in contrast to the common idea that a health record is an application-focused EHR or EMR. In the openEHR environment the emphasis is on the capture, storage, exchange and re-use of application-independent data based on shared definitions of clinical content – the archetypes and templates, bound to terminology. In openEHR we call them archetypes; in ISO, similar constructs are referred to as DCMs; and, most recently, there are the new models proposed by the CIMI initiative. It’s still all about the data!

So, we’re planning to showcase two products that have been designed and built to contribute to an openEHR-based health record - the Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM), as the collective resource for the standardised clinical content, and OceanEHR, which provides the technical and medico-legal foundation for any openEHR-based health record – the EHR repository, health application platform and terminology services. In addition, we’ll be demonstrating Multiprac – an infection control system that uses the openEHR models and is built upon the OceanEHR foundation. So Multiprac is one of the first of a new generation of health record applications which share common clinical content.

This will be interesting experience as neither are probably the sort of product typical attendees will be looking for when visiting the HIMSS exhibition. So therein lies one of our major challenges – how to get in touch with the right market segment… on a budget!

We are seeking to engage with like-minded individuals or organisations who prioritise the health data itself and, in particular, those seeking to use shared and clinically verified definitions of data as a common means to:

- record and exchange health information;

- simplify aggregation of data and comparative analysis; and

- support knowledge-based activities.

These will likely be national health IT programs; jurisdictions; research institutions; secondary users of data; EHR application developers; and of course the clinicians who would like to participate in the archetype development process.

So far I have in my arsenal:

- The usual on-site marketing approach:

- a booth - 13342

- company and product-related material on the HIMSS Online Buyers Guide; and

- marketing material – we have some plans for a simple flyer, with a mildly Australian flavour;

- Leverage our website, of course;

- Developing a Twitter plan for @oceaninfo specifically with activity in my @omowizard account to support it, and anticipating for some support from @openEHR – this will be a new strategy for me;

- And I’m working on development of a vaguely ‘secret weapon’ – well, hopefully my idea will add a little ‘viral’ something to the mix.

So all in all, this will definitely be learning exercise of exponential proportions.

To those of you who have done this before, I’m very keen to receive any insight or advice at this point. What suggestions do you have to assist a small non-US based company with non-mainstream products make an impact at HIMSS?

CIMI & beyond...

The Clinical Information Modelling Initiative (#CIMI) is currently meeting in London. It comprises a significant group of healthcare IT stakeholders and was formed some months ago as an initiative by Dr Stan Huff. After a number of face to face meetings and email list exchanges, the intent is that at the end of this 3 day meeting there will be an agreed decision on a common clinical content modelling formalism/methodology for our Electronic Health Records. For background, from Sam Heard’s email to the openEHR email list on November 2, 2011:

The main topic I want to address is the international initiative to develop a standardised clinical modelling methodology. This has some IHTSDO secretarial support and is led by Dr Stan Huff of Intermountain Healthcare, a former HL7 Chairperson and co-founder of LOINC, who has been advocating a model-based approach for many years. The current approach at Intermountain has been influenced by openEHR and uses a two-level modelling approach. Stan has established a leadership group through trust and reputation, which includes a variety of agencies who have been working in the area and national eHealth programs or major initiatives who are interested in consuming the models. It has grown out of an HL7 Fresh Look initiative and is currently known as the Clinical Information Modelling Initiative (CIMI).

The group has committed to determining a single formalism for clinical modelling and ADL and openEHR are on the list of alternatives which is as follows:

- Archetype Object Model/ADL 1.5 openEHR

- CEN/ISO 13606 AOM ADL 1.4

- UML 2.x + OCL + healthcare extensions

- OWL 2.0 + healthcare profiles and extensions

- MIF 2 + tools HL7 RIM – static model designer

Proponents of the five different approaches have been presenting to members of the group, who have a variety of experience in these matters. Fourteen organisations will cast a vote on the formalism to use including openEHR, Singapore, UK NHS, Results 4 Care, HL7, Canada Infoway, 13606 Association, Tolven, CDISC, GE/Intermountain, US Departments, CDISC, SMArt and Mitre.

At the preliminary vote, held recently on November 20, the two most popular options were openEHR ADL 1.5 and UML.

Today CIMI will vote on a proposal for either ADL 1.5 or UML to be adopted as the initial common formalism for use, and determine a road map for coordinated development of semantically interoperable clinical models into the future. The potential impact of this is huge and exciting. It could be a disruptive change in health IT.

We hold our collective breath!

The health information continuum

The final draft version of ISO 251's Technical Report "Personal Health Records — Definition, Scope and Context" has just been sent for formal publication. I was involved in some of the later drafting, especially proposing the notion of a spectrum, or continuum of person-centric health records was. The latest iteration, here:

Healthcare organisations and healthcare systems are accountable for the content of EHRs that they control. Individuals have autonomy over records they choose to keep. However, in between these two strict views of an EHR and a PHR is a continuum of person-centric health records which may have varying degrees of information sharing and/or shared control, access and participation by the individual and their healthcare professionals. Toward the EHR end of the spectrum, some EHRs provide viewing access or annotation by the individual to some or all of the clinician’s EHR notes. Towards the PHR end of the spectrum some PHRs enable individuals to allow varying degrees of participation by authorised clinicians to their health information – from simple viewing of data through to write access to part or all of the PHR.In the middle of this continuum there exist a growing plethora of person-centric health records that operate under collaborative models, combining content from individuals and healthcare professionals under agreed terms and conditions depending on the purpose of the health record. Control of the record may be shared, or parts controlled primarily by either the individual or the healthcare professional with specified permissions being granted to the other party.

And the final diagram:

Australia's PCEHR is an evolving example of a person-centric health record aiming for that somewhat scary middle zone of shared responsibility and mixed governance - carrying with it enormous potential for changing the delivery of healthcare and surmounting enormous clinical, technical, cultural and social challenges.

Australia's PCEHR is an evolving example of a person-centric health record aiming for that somewhat scary middle zone of shared responsibility and mixed governance - carrying with it enormous potential for changing the delivery of healthcare and surmounting enormous clinical, technical, cultural and social challenges.

What kind of things should we be considering?

How can we make the PCEHR a successful and vital component of modern healthcare delivery? What features and attributes will ensure that we steer clear of the approaches of previous failed projects and, instead, create some positive traction?

I've considered these issues for many years as I've watched the PHR/EHR domain wax and wane and I keep returning to 3 major factors that need to be considered from both the consumer and the clinician points of view:

- Health is personal

- Health is social

- Liquid data

These are the big brush stroke items that need to be front and centre when we are designing person-centric health records. Will post some more thoughts soon.

Archetype quality I

Up until recently clinical content models, such as archetypes, have been regarded as a novelty; watched from the sidelines with interest from many but not regarded as mainstream. However now that they are increasingly being adopted by jurisdictions and used in real systems, modellers need to change their approach to include processes, methodologies and quality criteria that ensure that the models are robust, credible and fit for purpose. There has been some work done identifying quality criteria for clinical models but there is no doubt that establishing quality criteria for clinical content models is still very much in its infancy:

- Kalra D, Tapuria A, Freriks G, Mennerat F, Devlies J (2008). Management and maintenance policies for EHR interoperability resources [36 pages] (Q-REC Project IST 027370 3.3 ). The European Commission: Brussels. (Last accessed May 28, 2011)

- There has been some slowly progressing work in ISO TC 215 - ISO 13972 Health Informatics: Detailed Clinical Models. Recently it has been split into two separate components, not yet publicly available:

- Part 1. Quality processes regarding detailed clinical model development, governance, publishing and maintenance; and

- Part II - Quality attributes of detailed clinical models

Most of the work on quality of clinical models has been based largely on theory, with few groups having practical experience in developing and managing collections of clinical models, other than in local implementations.

In 2007, Ocean Informatics participated in a significant pilot project. The recommendations were published in the NHS CFH Pilot Study 2007 Summary Report. My own analysis, conducted in December 2007, revealed that there were 691 archetypes within the NHS repository. Of these, 570 were archetypes for unique clinical concepts, with the remainder reflecting multiple versions of the same concept. In fact, for 90 unique concepts there were 207 archetypes that needed rationalisation – most of these had only two versions however one archetype was represented in five versions! We needed better processes!

Towards the end of 2007 a small team within Ocean commenced building an online tool, the Clinical Knowledge Manager to:

- function as a clinical knowledge repository for openEHR archetypes and templates and, later, terminology subsets;

- manage the life-cycle of registered artefacts, especially the archetype content – from draft, through team review to published, deprecated and rejected. Also terminology binding and language translations;

- governance of the artefacts.

In July 2008 we started uploading archetypes to the openEHR CKM, including many of the best from the NHS pilot project. Over the following months we added archetypes and templates; recruited users; and started archetype reviews. All activity was voluntary – both from reviewers and editors. Progress has thus been slower than we would have liked and somewhat episodic but provided early evidence that a transparent, crowd sourced verification of the archetypes was achievable.

In early 2010, Sweden's Clinical Knowledge Manager had its first archetypes uploaded.

In November 2010, a NEHTA instance of the CKM was launched, supporting Australia's development of Detailed Clinical Models for the national eHealth priorities. This is where most collaborative activity is occurring internationally at present.

In this context, I have pondered the issues around clinical knowledge governance now for a number of years, and gradually our team has developed considerable insight into clinical knowledge governance – the requirements, solutions and thorny issues. To be perfectly honest, the more we delve into knowledge governance, the more complicated we realise it to be – the challenge and the journey continues; a lot is yet to be solved :)

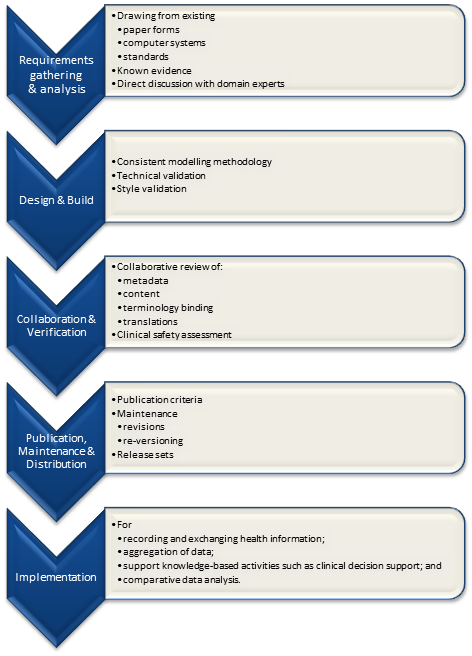

It is relatively easy to identify the high level processes in the development of clinical knowledge artifacts, each of which requires identification of quality criteria and measurable indicators to ensure that the final artifacts are fit for purpose and safe to use in our EHR systems. The process is similar for both archetypes and templates; plus the Requirements gathering and Analysis components are applicable to any single overarching project as well.

For archetypes:

The harder task is that for each of these steps, there are multiple quality criteria that need to be determined, and for each criterion it will be necessary to be able to assess and/or measure them through identifiable quality indicators.

Ideally a quality indicator is a measurement or fact about the clinical model. In some situations it will be necessary to include additional assessments manually performed by qualified experts.

If an indicator can be automatically derived from the Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM), it ensures that up-to-date assessments of the models are instantly available as the models evolve (such as this Blood Pressure archetype example), and more importantly, without reliance on manual human intervention. However while assessments that do need to be assessed by an expert human – for example, compliance to existing specifications or standards – add valuable depth and richness to the overall quality assessment, they also add a vulnerability due to the need for skilled human resources to not only conduct the assessment, but to apply consistent methodologies during the assessment; these will be much more difficult to sustain.

Assessment of whether the indicators actually satisfy the quality criteria should also ideally be as objective as possible, however our reality is that it will probably more often be subjective and vary depending on the nature of the archetype concept itself. The process cannot be automated, nor can there be a single set of indicators or criteria that will determine the quality of every archetype. We need to ensure appropriate oversight to archetype development, ensuring that a quality process has actually been followed and utilise quality indicators to determine if the quality criteria have been met - on an archetype by archetype basis.

Clinical modeling: academic vs practical

In a comment on the previous DCM post, Gordon Tomes sent a link to an interesting 2009 academic paper by Scheuermann, Ceusters & Smith - Toward an Ontological Treatment of Disease and Diagnosis [PDF] There is a place for this 'pure', academic approach as a means to seek clarity in definitions, but a telling sentence in the paper for me is: "Thus we do not claim that ‘disease’ as here defined denotes what clinician in every case refer to when they use the term ‘disease’. Rather, our definitions are designed to make clear that such clinical use is often ambiguous."

This is totally right, but despite the apparent ambiguity this clinicians still manage :)

The approach for archetypes/DCMs is not to get tied up in these definitional knots unnecessarily but to concentrate on consensus building around the structure of the data. Use of ontologies and definitions are key elements in designing and modelling archetypes but the resulting models should not be based on academic theory but on existing clinical practice and processes. Our EHRs need to represent what clinicians actually need to do in order to provide care. Sometimes we need to be practical and pragmatic. For example, I once challenged a dissenter to build a Blood Pressure archetype based purely using SNOMED codes - the result was a nonsense, a model that he agreed was not useable by clinicians.

The approach to building the Problem/Diagnosis archetype has not been to try to differentiate these two terms pedantically. Many have tried to separate a 'Problem' from a 'Diagnosis' for years with little success - no point waiting for this to be resolved, it probably won't. And even if we did make a theoretical decision on a definition for each, the clinicians would still likely classify the way they always did, not the way the academics or standards-makers would like them to do it!

In the collaborative CKM reviews for the NEHTA Problem/Diagnosis archetype we have been able to observe that clinicians and other stakeholders have achieved some consensus around the structured data required to represent the concepts of a problem plus the addition of some extra optional data elements to represent formal diagnoses. After completing only four review rounds, the discussion now is focused on finessing the metadata and descriptions, not on debating the structure of the model.

Clinicians may still go round in circles arguing about what constitutes an actual problem vs a diagnosis - for example, some may classify heartburn as a problem, others as diagnosis. No matter. By using a single model to represent both we can ensure that no matter how heartburn may be labelled by any individual clinician, we can easily query and find the data in a health record, and in addition there is a single common model to be referenced by clinical decision support engines.

A small success, maybe.

openEHR: interoperability or systems?

Thomas Beale (CTO of Ocean Informatics and chair of the Architecture Review Board of the openEHR Foundation) posted these two paragraphs as part of the background for his recent Woland's Cat post - The Null Flavour debate - part I. It is an important statement that I don't want to get lost amongst other discussion, so I've reposted it here:

An initial comment I will make is that there is a notion that openEHR is ‘about defining systems’ whereas HL7 ‘is about interoperability’. This is incorrect. openEHR is primarily about solving the information interoperability problem in health, and it addresses all information, regardless of whether it is inside a system or in a message. (It does define some reference model semantics specific to the notion of ‘storing information’, mainly around versioning and auditing, but this has nothing to do with the main interoperability emphasis.)

To see that openEHR is about generalised interoperability, all that is needed is to consider a lab archetype such as Lipid studies in the Clinical Knowledge Manager. This archetype defines a possible structure of a Lipids lab test result, in terms of basic information model primitives (Entry, History, Cluster, Element etc). In the openEHR approach, we use this same model as the formal definition of this kind of information is in a message travelling ‘between systems’, in a database or on the screen within a ‘system’. This is one of the great benefits of openEHR: messages are not done differently from everything else. Neither is interoperability of data in messages between systems different from that of data between applications or other parts of a ‘system’.

Engaging Clinicians in Clinical Content (in Sarajevo)

Just browsing and found the link to our presentation for a paper the CKM team gave at the Medical Informatics Europe conference in Bosnia, 2009. Thought I'd share it here, in memory of an amazing conference and location:

MIE09: Engaging Clinicians in Clinical Content [PDF]

Our presentation:

[slideshare id=1958920&doc=engagingcliniciansinclinicalcontent-090906091020-phpapp02]

And the reference to Herding Cats is explained (a little) in the embedded video - actually an advertisement for EDS:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pk7yqlTMvp8&w=425&h=349]

I arrived after a 37 hour flight - Melbourne - London - Vienna - Sarajevo to join my Ocean CKM team - Ian McNicoll and Sebastian Garde. We presented our paper and also ran an openEHR workshop.

The conference was held at the Holiday Inn in Sarajevo - the hotel in which all the international journalists were holed up during the war, on 'Sniper Alley'.

Despite it being 14 years after the war had ended, raw emotions were palpable many times during the conference. That a pan-European conference was being held in his beloved Sarajevo under his auspice was a very overwhelming event for the Professor of Informatics and he was often seen in tears!

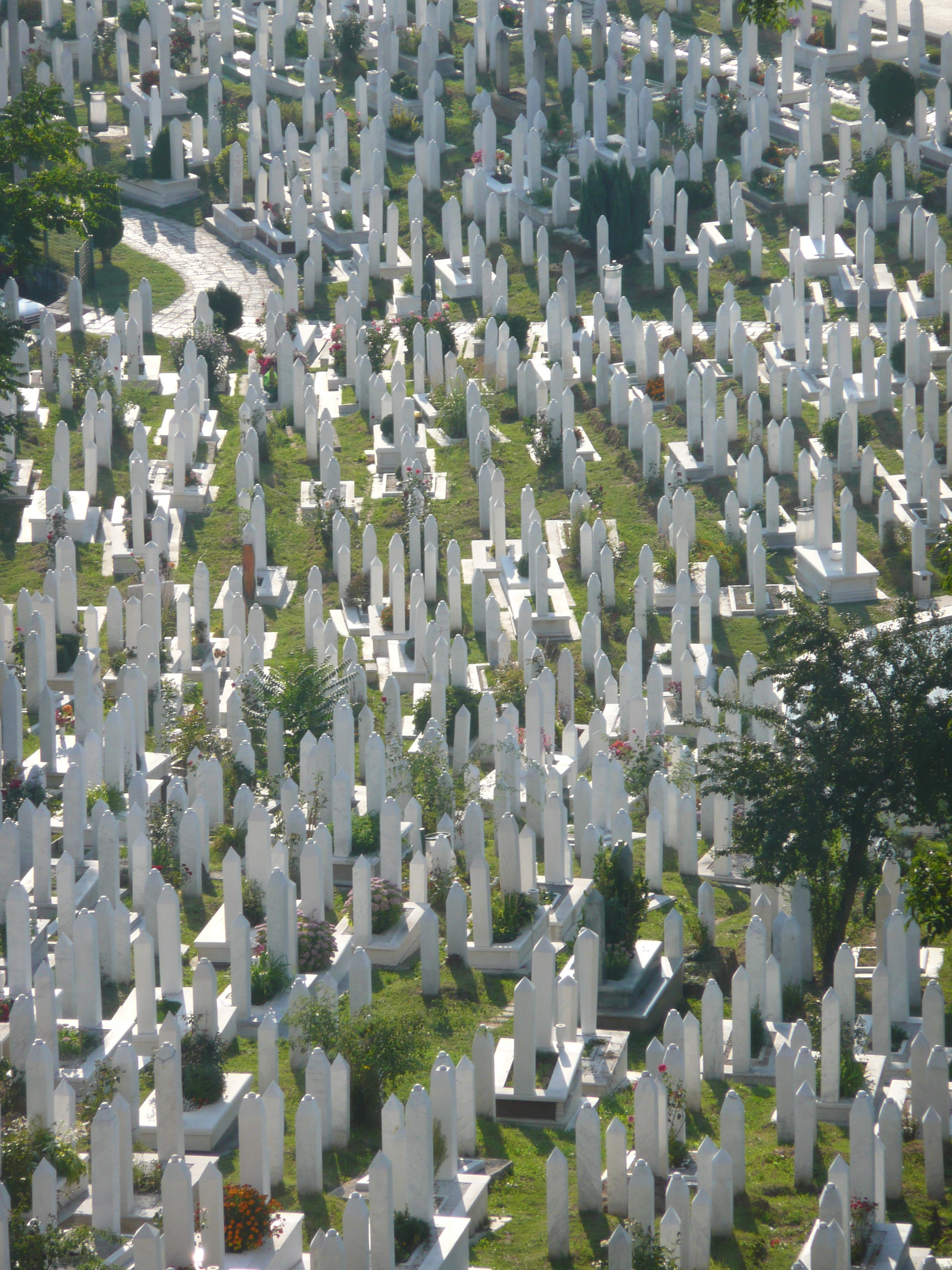

From my hotel room window in the centre of the city I could see 6 cemeteries.

Walking through the inner city we came across many cemeteries, thousands of marble gravestones with the majority representing the young men aged between 18 & 26.

Bullet holes were still very obvious on the walls of buildings.

Yet the city was vibrant, alive and welcoming.

I won't ever forget this visit.

Some photos of the experience: