Following on from the previous post...

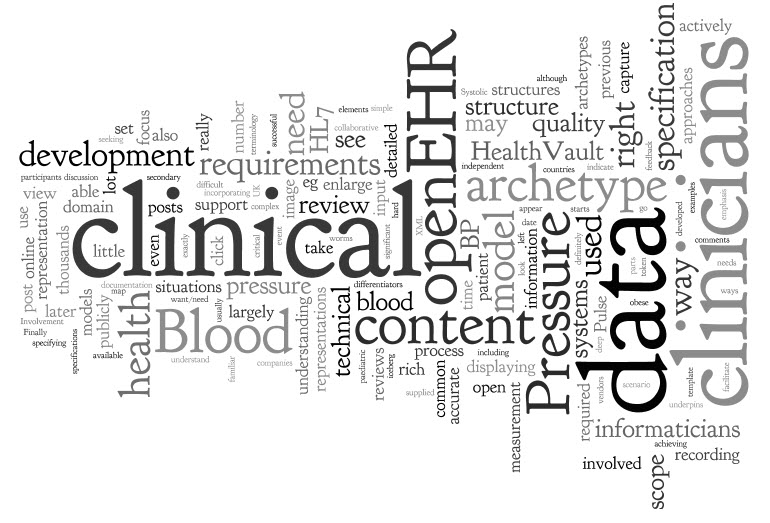

If we want to compare and review blood pressure (BP) over time from all sources and clinical situations, then they need to be recorded in a consistent manner. We also need a common structure to facilitate accurate data exchange without manipulation.

Following on from the previous post...

If we want to compare and review blood pressure (BP) over time from all sources and clinical situations, then they need to be recorded in a consistent manner. We also need a common structure to facilitate accurate data exchange without manipulation.

Most systems have a proprietary database comprising a home-grown data structure – so if there are 'n' thousands of clinical vendors in existence, there are probably way more than 'n' thousands of technical approaches to specifying the clinical documentation and process that are so familiar to you. HealthVault is one that publishes its data specifications publicly but most private companies are not so open.

There are also a number of approaches that are proposing use of common data structures to support health information sharing. You can see some of my thoughts on this in previous posts – and in my opinion this is definitely the way to go if you want/need to do smart and active things with health data. Some examples are HL7 templates and openEHR archetypes.

Let's take a look at some publicly available representations of Blood Pressure...

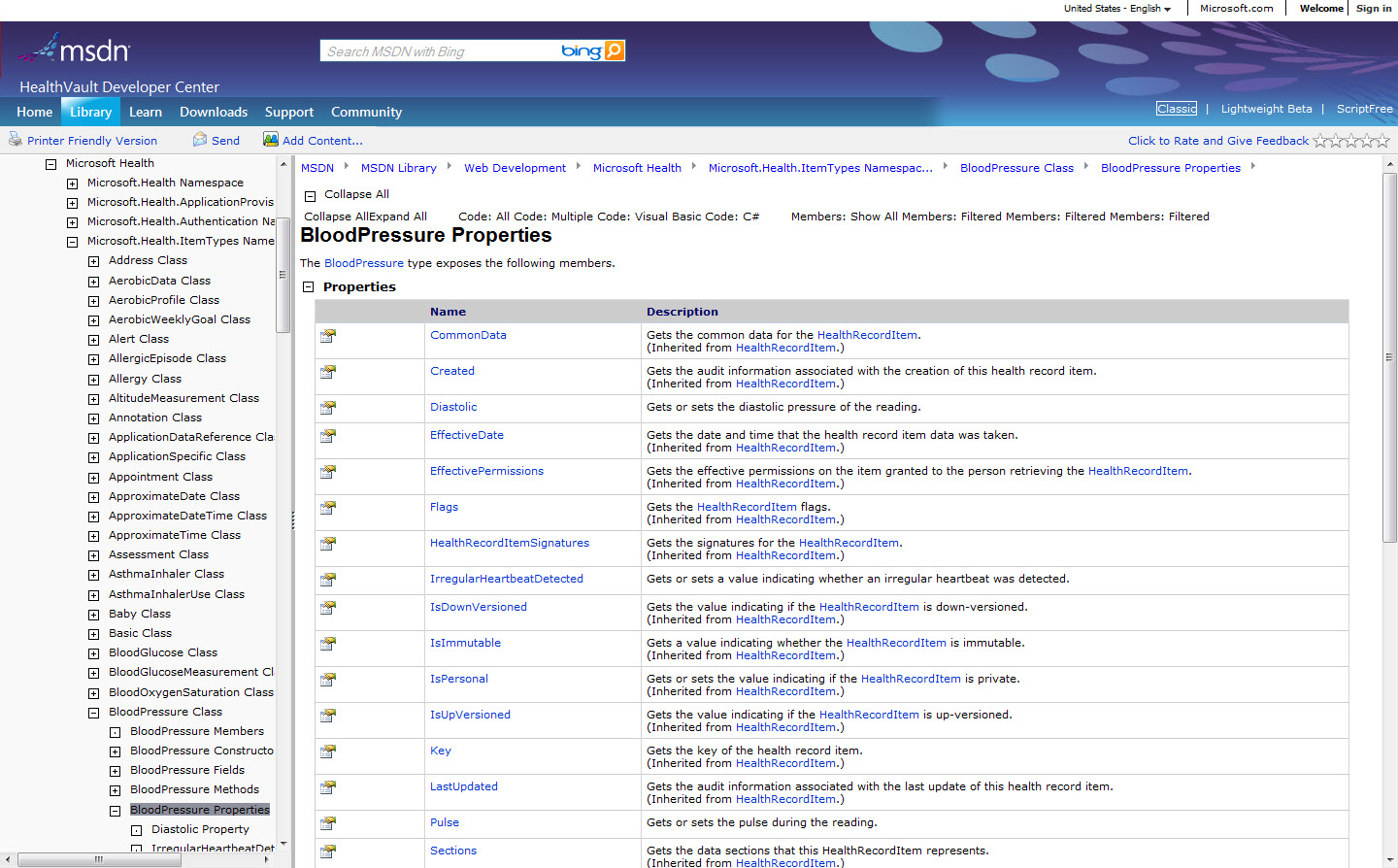

On the right is the Microsoft HealthVault Blood Pressure specification (click image to enlarge):

It's largely in 'techspeak', although if you examine the specification itself you will find only three clinical elements:

- Systolic

- Diastolic and...

- Pulse!

Ouch... Pulse is usually independent of BP measurement for most clinicians, even if it may commonly be measured simultaneously. This model cannot currently capture event the basice clinical requirements identified in the previous post - not even recording that a large cuff was used for an obese patient, to indicate whether the measurement is accurate and able to be interpreted confidently. This model is really not rich enough to cater with our clinical recording requirements for Blood Pressure.

At right is a HL7 model for Blood Pressure (click image to enlarge):

Umm... maybe a little difficult to understand. It's hard to see the scope of the content, and almost impossible for clinicians to have input into, which is a significant issue in terms of achieving accessible and high quality data definitions.

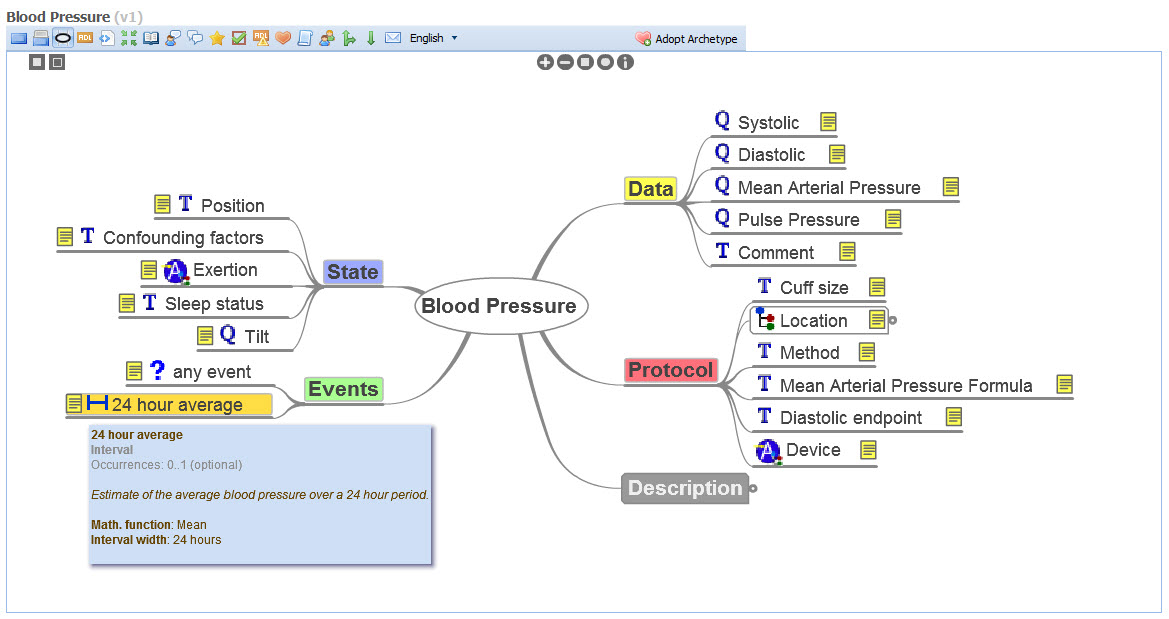

Finally, openEHR has a number of ways of representing the data model for Blood Pressure. It is a maximal data set intending to capture all information about Blood Pressure measurements for all the clinical and research situations described previously, and more.

On the right is the simplest representation of the openEHR blood pressure archetype – displaying the content in a non-technical way so that all clinicians can focus and comment on the clinical content itself.

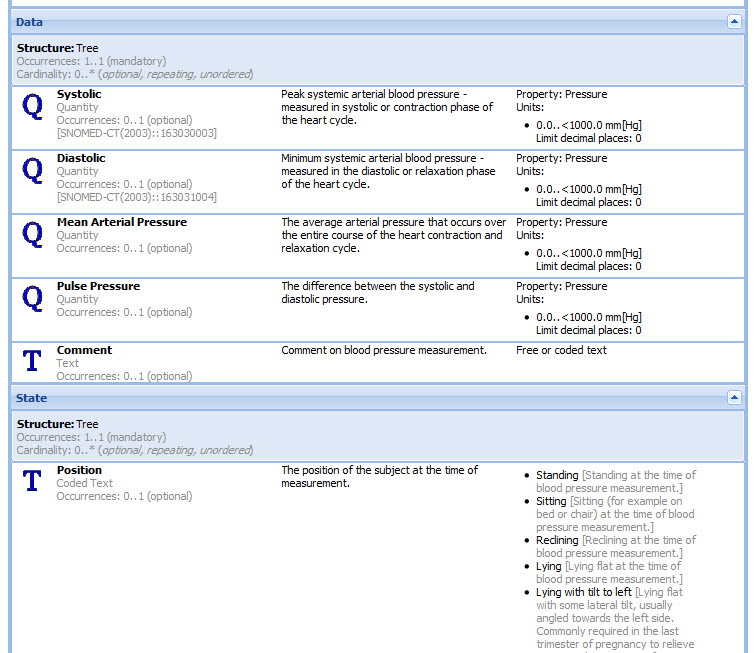

At right is another way that the same BP archetype is displayed to clinicians and informaticians - specifically used when seeking detailed comments about the clinical content on a per element basis during collaborative online archetype reviews. While it may help to have an understanding of data types eg Text or Quantity or Date, no deep understanding of openEHR is required of participants.

In the interests of full disclosure, I have been intimately involved in the development of the openEHR Blood Pressure archetype which has been developed and agreed with a lot of clinical input, and places a lot of emphasis on being approachable by clinicians and incorporating their feedback. The representations you see here are not perfect, but grassroots clinicians are participating actively in online reviews of archetypes. The blood pressure archetype was published after consensus was reached on the content by 30 clinicians, informaticians and engineers from 13 countries.

There is no doubt that at first glance the archetype may appear too rich. One of the key differentiators in openEHR is the capability to take this maximum data set and activate/display only the parts that are relevant to the clinical scenario requirements eg for primary care or a paediatric patient. This detailed discussion is out of the scope of this post, and will be left until a later date.

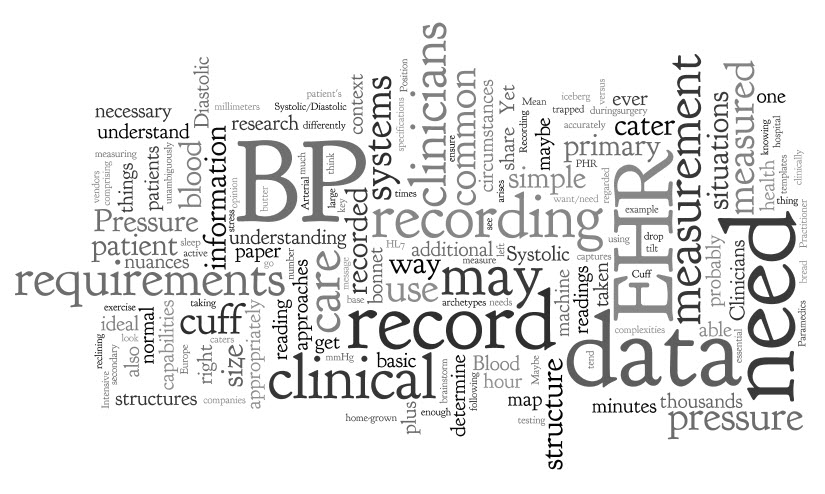

The focus of the health IT domain has largely been technical. Involvement of clinicians has often been token or as a secondary process. It is critical for successful development of EHR systems that clinicians are able to be actively involved in development and quality control of the clinical content that underpins these systems - clinicians need to request involvement. At the same time, the health IT domain needs to 'un-technify' eHealth - clinicians need support to participate, so that more than just a few elite informaticians can view these data structures and contribute to their development and quality review.

In these two posts we have explored a little about the scope of clinical models and their representation. Yet again, this is still only the tip of the iceberg re health data. The list goes on, including the use of terminology and the non-trivial technical requirements that are required to underpin these clinical models so that we have know exactly what this data means - far more complex than can be supplied by a simple XML model. Now that really starts to open a can of worms... for later!