Attending the International Council meetings on the first day of the recent Sydney HL7 meeting, the resounding theme was that of many countries focussed on messages, documents and terminology as the solution for our health IT future; our EHRs; health interoperability. 19 countries presented and 18 repeated this theme. The nineteenth HL7 affiliate, Netherlands, stood out in splendid isolation by declaring an additional focus on the development of clinical content.

Incremental EHRs?

This common message/document/terminology approach to EHRs is largely for historical reasons - safe, solid and incremental innovation; building on what has been proven successful before. It is not unique to health IT. It is not unique to HL7 either - it was just very obvious on the day.

In fact you can see this same phenomena in many places in everyday life - the classic example being the manufacturing of disposable shavers. First a one blade razor, then two blades, then three... But how long can this go on for? Is seven blades a reasonable thing? Eight? Will infinitely more blades make a difference to the shaving outcome or experience? When will blade makes stop and rethink their approach to innovation?

Certainly messages, documents and terminology are approaches that have commenced as often relatively isolated islands of work, had some successes, progressed and are now gradually being drawn together to create opportunities for some interoperability of health information. And don't get me wrong, there are absolutely some successes occurring. However, three questions linger in my mind about this approach:

- Is it enough?

- Is it sustainable?

- Will it achieve interoperable systems?

We all hear the rhetoric that if we can interconnect financial systems, then we can do it for health. We've tried this incremental approach for over 30 years and made significant progress but we definitely haven't cracked it yet.

Messages

Messages

Paul Roemer used this diagram (right) to illustrate his view of the messaging exchanges in his blog post. I think the image is powerful, imparting both the complexity and chaos that an n-to-n messaging dependency will likely entail. The HIE approach might help, but ultimately a national approach to messaging will result in multiple images like this trying to connect to each other.

This is further complicated by messages often taking up to a year to negotiate between the sender and receiver, or potentially longer to successfully negotiate the national or international standards processes, and even then the resulting 'standard' is often being subjected to individual tweaks and updates at implementation in real-world systems where the 'one-size fits all' message doesn't meet the end-user's requirements.

In Australia the 'standard' pathology HL7 v2.x message is anything but standard with each clinical system vendor having to support multiple slightly different versions of the 'standard'. The big question is whether this is sustainable into the future.

In the US, the clinical content payload for the Direct project is yet to be determined and defined - "The project focuses on the technical standards and services necessary to securely transport content from point A to point B, and does not specify the actual content exchanged." This rings alarm bells for me.

I've been told that at one relatively large hospital system in the US, they require 30 permanent staff just to maintain their messages...! Whoa!!!

Messages and message networks try to be a simple incremental solution to interoperability. But are they really that simple? Are they sustainable? Locally, yes. Regionally, yes probably. Nationally? Internationally???

<My head hurts>

Documents

CDA documents featured highly on the HL7 agenda, with the current emphasis on simple documents, and increasingly we will welcome the inclusion of structured clinical content detail. Currently the content is HL7 v3 templates, but how will that content be standardised and support semantic interoperability?

Werner Ceusters describes semantic interoperability as:

Two information systems are semantically interoperable if and only if each can carry out the tasks for which it was designed using data and information taken from the other as seamlessly as using its own data and information.

Without working towards standardising clinical content we run the risk of our EHRs being little more than a filing cabinet full of unstructured documents that are human readable but not computer processable.

Terminology

We all need terminology, no matter which approach. That is an absolute given.

However the stand-out question that impacts all approaches is how to best 'harness' the terminology...

Interestingly the openEHR Board and the IHTSDO Management Board (SNOMED CT) have been talking about joining forces. An announcement on the openEHR site, in December 2010, states:

"At its October meeting in Toronto, the General Assembly of the IHTSDO received and discussed a proposal, submitted by its Management Board, to support, develop and maintain the IP in openEHR, within a broader framework of IHTSDO governance for clinical content of the electronic health record.

The openEHR Foundation Board has now heard from the IHTSDO Management Board, saying that, whilst the objective of the proposal was considered by the GA to be within the scope of the organisation and that it represented a pressing issue for their governments, it was unable to reach consensus that going forward with openEHR in this way is the right choice, at this time."

This suggests that the IHTSDO Management Board identified significant value in combining the structure of openEHR archetypes with SNOMED, enough to propose a stronger relationship. It will be interesting to see if these discussions continue to progress.

My view - this would be a game-changer. A common approach to using archetypes and SNOMED together is a potentially very powerful semantic combination.

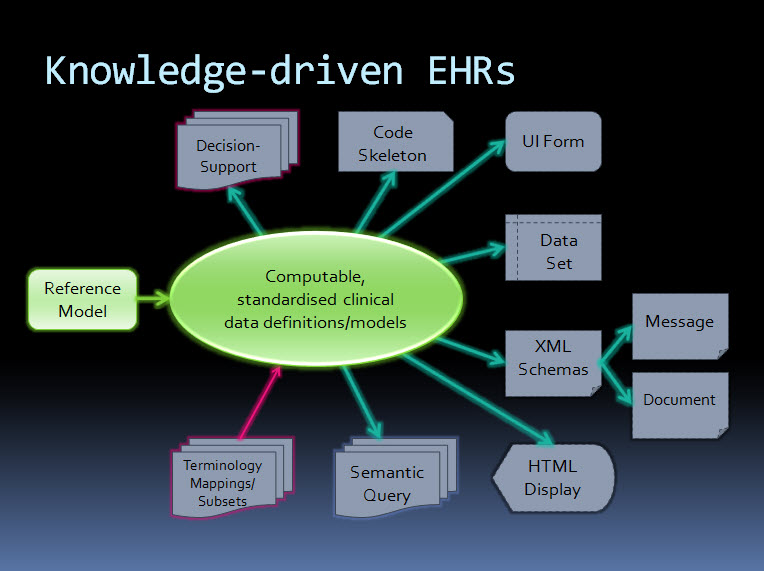

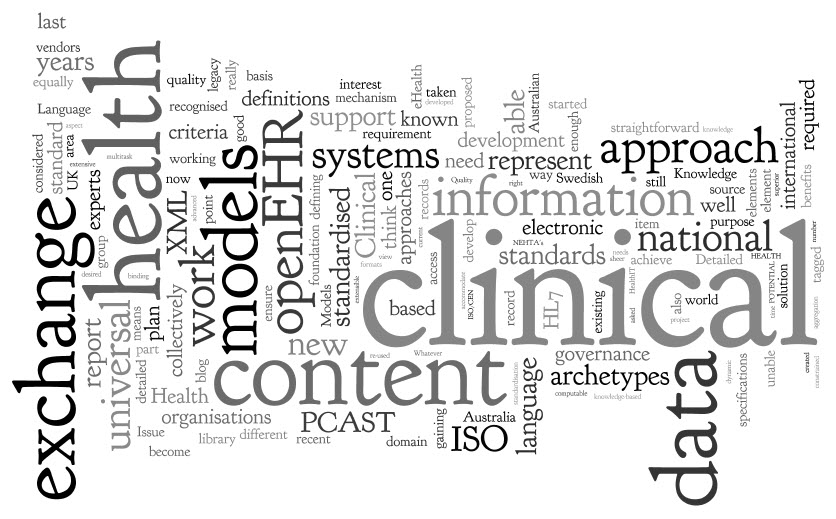

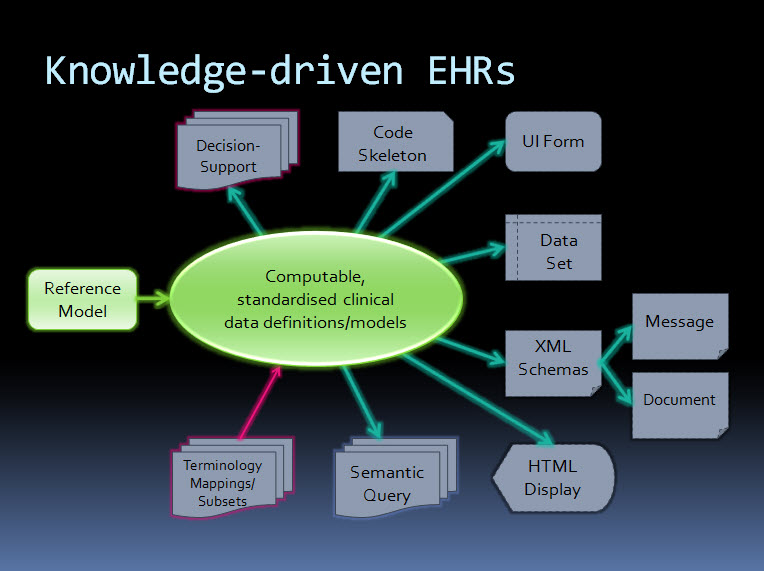

An orthogonal approach - knowledge-driven EHRs

By contrast, the orthogonal approach taken by ISO 13606 & openEHR starts with computable, standardised clinical data definitions at the core - representing the clinical content within an electronic health record. The data definitions, comprising archetypes plus terminology, are the key. Messages and documents are derived from these content specifications and will therefore be internally consistent with the EHR data from which they were generated and if received into an archetype-enabled system can be incorporated, as described by Werner's definition above, as though generated in the receiving system ie semantic interoperability - no data transformation required. The openEHR communities of clinicians, informaticians and engineers are collaborating to agree and standardise these archetypes as a common starting point.

Working from standard content definitions will potentially make the development of documents and messages orders of magnitude simpler. If archetypes have been agreed and published via the CKM collaborative process, then engineers will be able to utilise these as building blocks for the creation of messages and documents for specific use cases, and for a multitude of other technical outputs.

The way forward?

Returning to the multi-blade EHR idea...

When will we stop, regroup and assess the merit of continuing as we are? Who will draw a line in the sand?

Difficult to answer.

Maybe never, maybe no-one.

openEHR/ISO 13606 may not be the right or final answer, but it does provide an alternative and orthogonal approach that has merit and is worth consideration.

Hopefully some of outcomes/proposed discussions from the recent HL7 meeting in Sydney will also contribute to clarifying a way forward.

Perhaps, even yet, we will devise a truly innovative approach to solving the difficulties of developing EHRs.