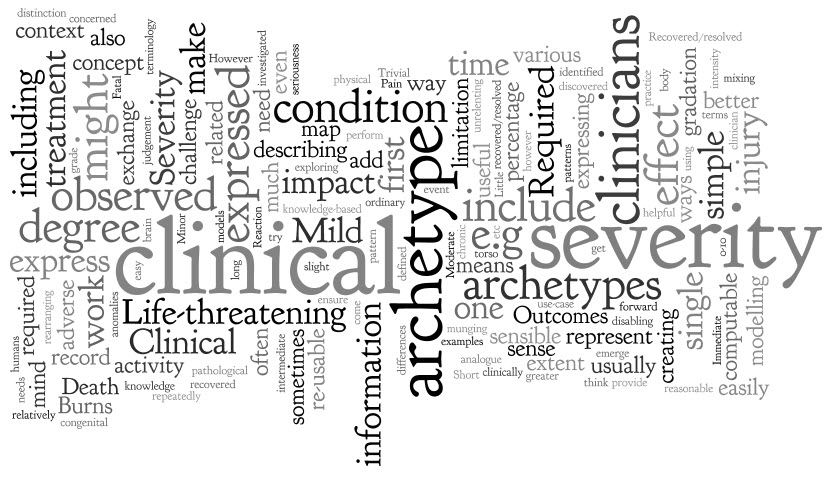

Up until recently clinical content models, such as archetypes, have been regarded as a novelty; watched from the sidelines with interest from many but not regarded as mainstream. However now that they are increasingly being adopted by jurisdictions and used in real systems, modellers need to change their approach to include processes, methodologies and quality criteria that ensure that the models are robust, credible and fit for purpose. There has been some work done identifying quality criteria for clinical models but there is no doubt that establishing quality criteria for clinical content models is still very much in its infancy:

- Kalra D, Tapuria A, Freriks G, Mennerat F, Devlies J (2008). Management and maintenance policies for EHR interoperability resources [36 pages] (Q-REC Project IST 027370 3.3 ). The European Commission: Brussels. (Last accessed May 28, 2011)

- There has been some slowly progressing work in ISO TC 215 - ISO 13972 Health Informatics: Detailed Clinical Models. Recently it has been split into two separate components, not yet publicly available:

- Part 1. Quality processes regarding detailed clinical model development, governance, publishing and maintenance; and

- Part II - Quality attributes of detailed clinical models

Most of the work on quality of clinical models has been based largely on theory, with few groups having practical experience in developing and managing collections of clinical models, other than in local implementations.

In 2007, Ocean Informatics participated in a significant pilot project. The recommendations were published in the NHS CFH Pilot Study 2007 Summary Report. My own analysis, conducted in December 2007, revealed that there were 691 archetypes within the NHS repository. Of these, 570 were archetypes for unique clinical concepts, with the remainder reflecting multiple versions of the same concept. In fact, for 90 unique concepts there were 207 archetypes that needed rationalisation – most of these had only two versions however one archetype was represented in five versions! We needed better processes!

Towards the end of 2007 a small team within Ocean commenced building an online tool, the Clinical Knowledge Manager to:

- function as a clinical knowledge repository for openEHR archetypes and templates and, later, terminology subsets;

- manage the life-cycle of registered artefacts, especially the archetype content – from draft, through team review to published, deprecated and rejected. Also terminology binding and language translations;

- governance of the artefacts.

In July 2008 we started uploading archetypes to the openEHR CKM, including many of the best from the NHS pilot project. Over the following months we added archetypes and templates; recruited users; and started archetype reviews. All activity was voluntary – both from reviewers and editors. Progress has thus been slower than we would have liked and somewhat episodic but provided early evidence that a transparent, crowd sourced verification of the archetypes was achievable.

In early 2010, Sweden's Clinical Knowledge Manager had its first archetypes uploaded.

In November 2010, a NEHTA instance of the CKM was launched, supporting Australia's development of Detailed Clinical Models for the national eHealth priorities. This is where most collaborative activity is occurring internationally at present.

In this context, I have pondered the issues around clinical knowledge governance now for a number of years, and gradually our team has developed considerable insight into clinical knowledge governance – the requirements, solutions and thorny issues. To be perfectly honest, the more we delve into knowledge governance, the more complicated we realise it to be – the challenge and the journey continues; a lot is yet to be solved :)

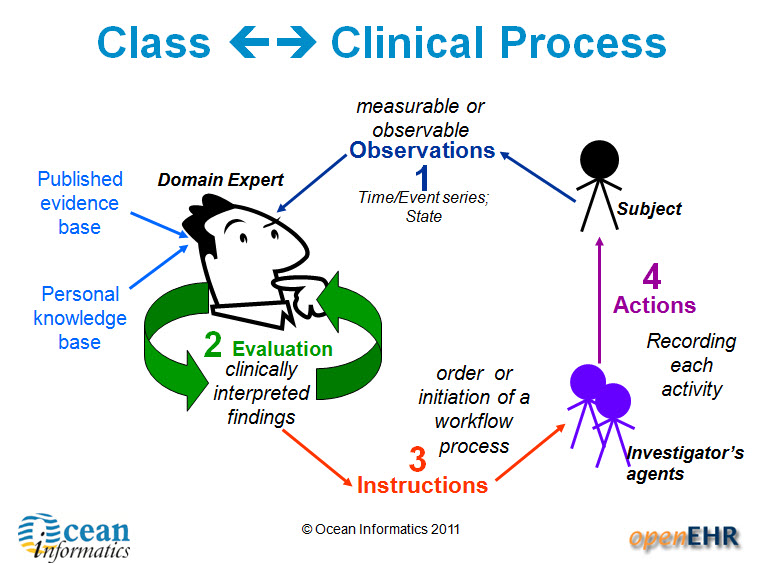

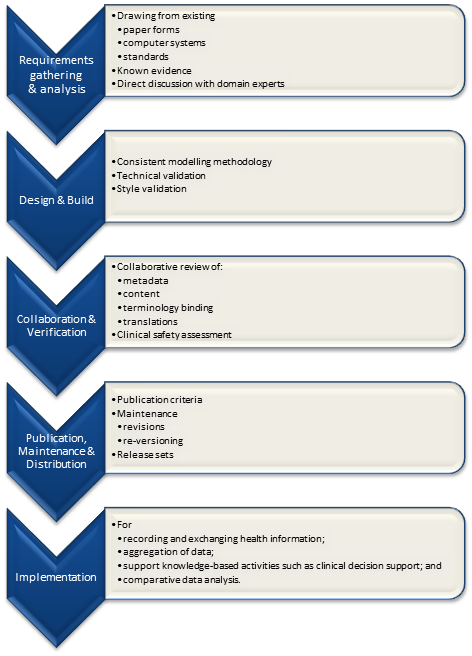

It is relatively easy to identify the high level processes in the development of clinical knowledge artifacts, each of which requires identification of quality criteria and measurable indicators to ensure that the final artifacts are fit for purpose and safe to use in our EHR systems. The process is similar for both archetypes and templates; plus the Requirements gathering and Analysis components are applicable to any single overarching project as well.

For archetypes:

The harder task is that for each of these steps, there are multiple quality criteria that need to be determined, and for each criterion it will be necessary to be able to assess and/or measure them through identifiable quality indicators.

Ideally a quality indicator is a measurement or fact about the clinical model. In some situations it will be necessary to include additional assessments manually performed by qualified experts.

If an indicator can be automatically derived from the Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM), it ensures that up-to-date assessments of the models are instantly available as the models evolve (such as this Blood Pressure archetype example), and more importantly, without reliance on manual human intervention. However while assessments that do need to be assessed by an expert human – for example, compliance to existing specifications or standards – add valuable depth and richness to the overall quality assessment, they also add a vulnerability due to the need for skilled human resources to not only conduct the assessment, but to apply consistent methodologies during the assessment; these will be much more difficult to sustain.

Assessment of whether the indicators actually satisfy the quality criteria should also ideally be as objective as possible, however our reality is that it will probably more often be subjective and vary depending on the nature of the archetype concept itself. The process cannot be automated, nor can there be a single set of indicators or criteria that will determine the quality of every archetype. We need to ensure appropriate oversight to archetype development, ensuring that a quality process has actually been followed and utilise quality indicators to determine if the quality criteria have been met - on an archetype by archetype basis.